05 Jun Biotech firm thinks it has the most active antiviral targeting COVID-19 in development

Patrick Amstutz, PhD, CEO and Co-Founder, Molecular Partners, outlines the company’s pioneering new modality for custom-built medicines

You have been CEO of Molecular Partners since November 2016 and have been an important player in the Swiss biotech scene for a number of years. How would evaluate the evolution of the Swiss biotech landscape over the past 15 years? What is unique about Switzerland, its research and development (R&D), and its innovation?

Next to our banking sector, innovation has been the fuel for development in Switzerland. We don’t have oil or coal, and so innovation is the “oil” of Switzerland. We have a really good ecosystem with great universities, such as Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), ETH in Zürich and the Biozentrum in Basel. We also host two large pharmas, Novartis and Roche, which play an important role in life science. So, on the one hand we have a good level of innovation thanks to our excellent universities, and on the other hand, we have a good understanding on pharma, which creates a good ground for a flourishing biotech sector.

Biotech is a young industry and I think Switzerland offers the perfect setting to develop it. There are also good labor laws, a lot of money and investors, and people that believe in innovation. Besides, Switzerland has a good and functioning healthcare system, where people value good drugs, so that is an additional asset that sets up success for biotech.

According to your annual report for fiscal year 2019, the group recognized revenues of $21.3 million, an increase of 97 percent compared to the previous year, as a result of its partnership with the U.S. multinational biopharmaceutical company Amgen. Can you tell us more about the company’s growth and development over the last 16 years? What have been the major milestones and achievements of Molecular Partners?

We are in fact more in a cash burning industry, because biotech invests a lot in patient value, and what we want to measure is patient value. Our $21 million revenues measure the deal but not the business—our business is to create value for patients and that is what we measure.

Molecular Partners started as a spin off from the University of Zürich with the bold idea of using what we were researching then to generate value for patients. We like to say that we want to move the needle of medicine for patients with a serious disease like cancer. Cancer is one of our focus areas—although our first drug, which is already filed for approval in the U.S., EU and Japan, was developed to target a common cause of vision loss. The area we were focusing on back then was repeat proteins. Repeat proteins are nature’s answer for multi-specific binding proteins—it is a custom-built protein design and a novel therapeutic modality, or novel therapeutic proteins. What we aim to do is to build a molecular team in order to have one drug with several functions and not one drug for one function only. In oncology, which is a complex disease, it makes sense to have several players in one drug. Molecular Partners’ DARPin platform allows exactly that. To hit the virus with one player is OK but if you can hit it from three sides at the same time, that’s much more powerful. We have created the technology that allows this to happen.

That was the initial idea, back in 2004. We had to do Series A financing in startup phase. I was myself in the lab working at the bench—doing business deals and pipetting at the same time. We did a Series A financing round and raised $19.3 million, which was a big round back then. We grew the company to around 30 or 40 people, and then entered clinical development with our first candidate, which is now almost at approval. That drug has been filed in the U.S., which then opened the door for a Series B investment of around $42 million, which brought us to the stage of becoming an oncology company. In 2014, we had an initial public offering that raised about $111 million and we are now have over 140 people working in oncology, with a very new focus in virology to fight COVID.

In parallel to these investment, we also did deals, out-licensing deals, collaboration deals, and brought in more than 200 million Biodose collaborations, to cross fund what we were doing in oncology. We have evolved from a three-person company (we were actually six founders at the beginning) into what is now a 150-people company, spanning everything from the idea, to clinical development and up to clinical proof of concept. The next stage will be later clinical development and then commercial.

We would like to understand more about your technology and its uniqueness. How do your therapeutic treatments differentiate your company from other biotechs in general and what is special about it?

I think the key differentiation is the technology. The basis of Molecular Partners is our DARPin technology. DARPins are custom-built proteins designed into novel therapeutic modalities. As I said before, we aim to build a molecular team in order to have one drug with several functions, not just one. DARPin allows you to do molecular teams: one DARPin module can target one biological target in your body. Two can target two, and so on. Then you bring things together and you coactivate. It’s a bit like a Swiss Army knife with different functions, where you can bring in the different functions you need. Let’s say you’re attacking a tumor and you want to have local activity. This is maybe a key we are looking at in oncology.

Individual drugs work well in oncology, but you administer them and then they are active in the whole body. If you take an oral drug, or give an intravenous infusion, this drug will react wherever it is. What we are trying to do is create a sequence of DARPins that creates local activity. You get a form of the drug that by itself is not active, but it is active as a team when it hits the tumor. Systemic activity comes with systemic side effects and, as you know, in cancer the side effects are quite strong. A lot of these drugs are limited by the effect and side-effect profile. Our aim is to create a local super-active drug to combine activities at the tumor that would be too toxic to be given systemically. We are also administering systemically but not active systemically.

The molecular teams help each other to create a local activity over systemic activity, to create a more active drug and then, hopefully, to defeat cancer in the end. This is the idea we are following in cancer. COVID is a bit different and we can touch on that later. In cancer, it is about creating local super-activity by multi-specificity.

Moving on to the COVID-19 crisis and its implications, Molecular Partners is currently working on a therapy for coronavirus. Can you tell us about the progress you are making in this area and how your therapy differentiates from other approaches?

We started rather late in the game. Around ten weeks ago, when the virus was hitting Italy, we started to understand that this was a global threat. One of our board members, William Lee, was a Senior Vice President at U.S.-based Gilead Sciences, a virology research company. We asked him what he thought and he said that our approach could make a big difference—because we are oncologists and we had several key elements to add to the mix. One is our multi-targeting; the other is the speed we can move at and the fact that we can go for large-scale manufacturing, which means lower costs and higher volumes.

If you think you have a drug, you will need to distribute it throughout the world—DARPins can help there. Ideally, you can actually apply this with a simple subcutaneous injection. This is much easier and a doctor can apply it much faster than they could with an intravenous infusion, which is how Remdesivir is given today.

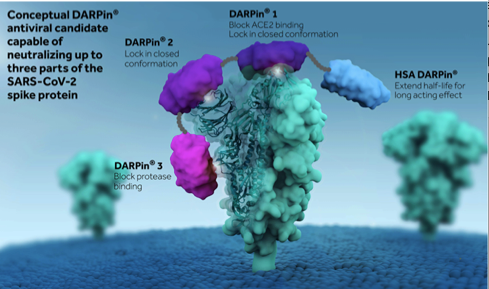

As you can see on this graphic:

The little blue dots represent the surface of the virus and the green spikes are the proteins, which the virus needs to infect or attack human cells. On the top there is a site that makes contact with a human cell, actually a specific receptor. The spike opens the door and the virus infects the human cell. If you have a DARPin 1 that binds where the virus should be binding with the human cell, the virus cannot recognize the human cell and is blocked. That is DARPin 1.

If this should happen and the virus still recognizes the human cell, the green protein has to open. The movement is like a door lock that you have to turn. If you hook up DARPin 1 and 2, you can think of it like a molecular handcuff. You are blocking the door by putting a little thing under the door that blocks the door from opening. The third step is that you actually have to turn the key, which is a protease that attacks, binds and cuts the protein so that it opens. All three of these mechanisms are needed by the virus to infect the cell. All other drugs, more or less, target what DARPin 1 is doing. DARPin 2, the molecular handcuff and blocking the door are mechanisms that others have not followed as fast.

What we did is we took the green protein and we selected DARPins 1, 2 and 3. Then we can put them together in one, to make one drug. That is what I call the molecular team: DARPin 1 does something, DARPin 2 does something and DARPin 3 does something. Together, they all hold onto the site protein.

In addition, there are two effects that happen. First, because they are all holding on together. It’s like a climber on a Swiss wall who has only one hand—that is tough. If the climber has three hands, they can climb much faster because they can hold here, let go there, hold again, and never lose contact. We were able to rapidly screen thousands of potential DARPins for activity against the virus. We identified the most potent DARPins and combined them into one drug. This allows for what we call cooperative or synergistic binding, which leads to much tighter binding. What we have is the most potent binder, the most potent inhibitor in the world made by the Swiss to bind and inhibit the virus. Based on the literature we have seen so far and from the data we have on the live virus, we believe we are the most active antiviral that’s in development right now.

In parallel to that, viruses mutate. If this virus should mutate on position one, you still have two DARPins that block it. If the next generation of virus comes back in the winter, for instance, this drug will likely still work because COVID-19 will not have mutated everything at once. It gives you a higher potency and prevents mutational escape by the virus. These two elements make this approach unique. We selected literally hundreds of DARPin 1s, DARPin 2s and DARPin 3s. We hooked them up in several different teams, and we selected those teams that acted synergistically and blocked the virus much better than anything else. When combined, these molecules create synergy and activity that others cannot get.

It’s quite fascinating: on the one side you have a little blue DARPin, called HSA DARPin, that leads the others to the virus, and human serum albumin (HSA), which leads to human blood and into the lungs. This will bring the other DARPins to where they have to be active. It’s like a messenger DARPin. It’s a nice illustration of how a molecular team works.

How do you think this pandemic will change the research landscape of Switzerland? Do you think it will accelerate some of its transformations or research in certain fields?

This virus has reminded all of us what our work is about: it’s about helping patients and supporting society. I think the virus is the best change management agent we could have had and this has come very fast.

We are working with two academic working groups, we are working with the Swiss Army and we are getting support from two industry leaders on this program. In other situations, we would still be filing non-disclosure agreements and fighting around little terms and termination clauses! Here, we don’t have any of that: we can do what is right to work together to help patients. This has reminded us that we need less lawyers and more trust, and that we need to work together to fight disease. I think this has happened in Switzerland, but it has also happened throughout the globe.

Molecular Partners is working with one group in Utrecht in Germany and another in the U.S. This global pandemic situation has accelerated global collaboration, and has helped open our dialogue with the government and Swiss medics. They are very supportive of what we are doing and we are also supporting them—a stronger collaboration or synergy has developed since we are on the same side. We have one common intruder, one virus that we have to attack, and it is uniting us on the other side of healthcare. This is a great thing to happen!

The COVID-19 situation has also impacted our company—internally, people are highly motivated. They are working day and night, they are working shifts, they are not taking a passive stance, but they are doing everything they can do make this drug happen.

Looking to the future, what kind of partnerships do you hope to capitalize on to continue the expansion of your company?

Partners is part of our name and our DNA. We like to do partnerships and always put the patient at the center. Whatever partnership will help us to gain more patient value, we will go for. In the beginning, when we were a younger company, we out-licensed a drug to the global pharmaceutical company Allergan, a business partner that has now filed it with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. We could not run global clinical trials in ophthalmology. That’s why a partnership was the way to go.

From there we went into a collaboration with Amgen, which is a co-development so we are taking more responsibility. Going forward, that’s where we want to evolve to—we want to be on a more equal partnership rather than an out-licensing partner, but always working for the benefit of a patient. We will see much more of that in the future as our platform literally can be applied in so many places. This is a new drug modality and we don’t want to hinder it from reaching its full potential in all applications. Partnering is going to be key for us moving forward.

What kind of next-level innovations or disruptions can we expect from Molecular Partners in the future? What sort of new treatments or discoveries are in your pipeline?

We have three activities in oncology. The first is tumor-specific agonists or immune cell regulators in which we can activate an immune system in the tumor. The second that we want to have is more precision targeting of tumors with novel tumor antigens. That is an area where we are targeting peptide MHCs for more precise targeting. The third is chrome drug: having drugs that are not active yet but get activated in the tumor.

Those three areas we want to pioneer and reach critical proof of concept in the coming years. Then, as the COVID program showed, there are applications that, for us, are imperative to act on. We want to do that ourselves but also enable partners to find applications where the DARPins can open a door or where you need a molecular team for patient benefit to see more of that happening.

What is your final message to the readers of Newsweek?

At Molecular Partners, we believe in innovation. We believe in Switzerland, and we believe that innovation and the support here that surrounds innovation—including universities, pharma and the Swiss Biotech Association—can drive innovation to value for patients. That’s what counts.

We can bring value to the patients ourselves and with partners. We can make a big difference for patients that have diseases today that are undertreated or that don’t have good solutions, such as cancer, or also in a situation like a global pandemic. This innovation is real. These products are becoming real and they will make a difference for patients in the future. We are all working very hard on this.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.